What Does the "Chi" in Your Name Mean?

My good friend, Chiamaka is always excited to tell non-Igbo people who care to ask that her name means, “God is Awesome.” “Chi” is, by far, the most used word in Igbo names. And the default assumption, of course from a very Christian perspective, is that “Chi” means “God.” Does it really? The Igbo word, “chi,” can mean god/God, but it can also mean other things. What though is the problem with the default that “Chi dị mma” means “God is good?” The majority of Igbo people now identify as Christians. For most Christians, the word “god” is narrowly understood from the perspective of the Abrahamic tradition where there is only one good god (always spelled with a capital letter “G,” and these other gods (always spelled with small letter “g”). The good “God” is loving, benevolent, and omniscient. He is the creator of heaven and earth and all good things come from him.

As for all the other gods, they really don’t have much to offer. They are at best ineffectual and at worst, the opposite of the good God. That is how most Christians, including Igbo Christians perceive divinity. But for the rest of humanity, including our pre-colonial ancestors, divinity is vast. For our ancestors, the word “chi” had always referred to (divinity) even before the Christian God was in the picture. Our ancestors were also polytheist. They did not believe in one universal divinity (or God) as is the case in the Abrahamic tradition. Prior to the arrival of European colonial missionaries, therefore, “chi” was used to designate various other-than-human entities. Did that change with the arrival of Christianity?

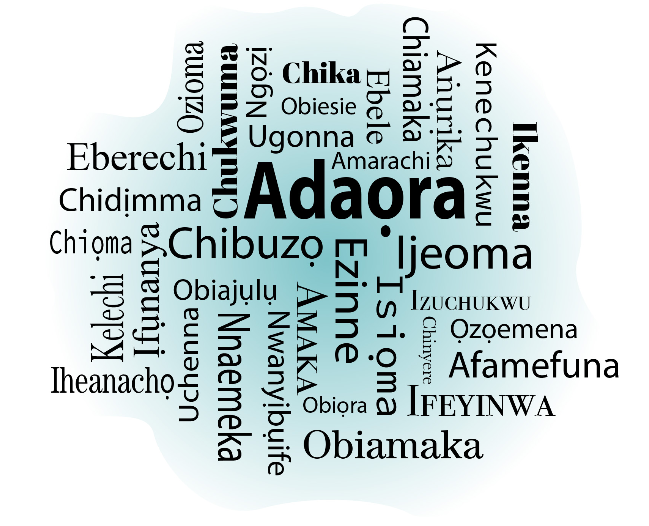

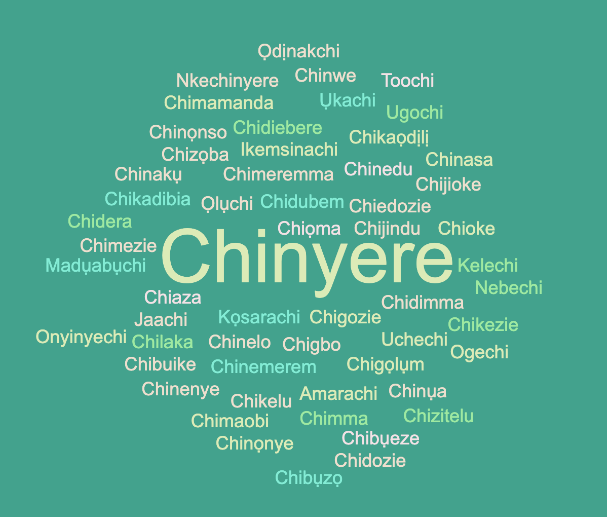

When the missionary band of European colonizers undertook the task of translating the bible to Igbo, they understood the Igbo language well enough to determine that “Chi” was not a suitable translation for “God.” That was the case because even a capitalized “Chi” could never mean one particular god/God. “Chi” is rather a category for deities and various other unseen forces. For example, our cultural and literal ambassador, Chimamanda Adichie once rendered her name in English as, “My Personal Spirit will Never Fail.” Note that her translation of “chi,” as used in her name, is, “my personal spirit.” Another person called Chimamanda, and with a Christian perspective may also translate the name as, “My God will Never Fail” and she would be in her right to do so. What I am trying to illustrate is that “chi” does not mean “God,” as in, the Almighty Christian God. It means more than just that.

It may also interest you to know that the Igbo pantheon contains a creator god called, “Okike,” "Eke," “Chukwu Okike,” or variants of that. There is also “Chukwu,” a contraction of the “Chi Ukwu” (The Great God). When European Christians began translating the bible to Igbo, they shied away from using “Chi” as a suitable translation for “God.” They also did not use "Okike," "Eke," "Chukwu," or "Chukwu Okike" to translate "God." Instead, they coined a new term, "Chineke" (chi na-eke), literally, “the god who creates” or “The Creator God.” When it comes to the spelling of Chineke, they also followed the biblical tradition and rendered this word consistently with with a capital letter "C." It follows, therefore, that the only Igbo word for the Christian God is “Chineke.” Note that Chineke never gets abbreviated to “Chi;” it is always written in full, “Chineke,” so as not to have it confused with any other "chi"/"god."

In addition, the Igbo bible generously used God’s personal name, “Jehova” in all the relevant places. It is important to have this context because, from the Igbo cosmological perspective, “Chi” can also include the Christian God as a divine being. But from the Christian theological view, that would be a misnomer because “Chi” does not exclusively refer to the god of Abraham spelled consistently with a capitalized “G." Keep in mind, too, that our ancestors began naming their children with all these “chi” names long before they knew about the “God” of European Christians. Therefore, it would be anachronistic to conclude that their use of “chi” was in reference to the Christian “God.” “Chi” was in use long before the Christian God was introduced to them.

The problem is even compounded when you consider that Europeans themselves did not accept “Chi” (capitalized or not) as a suitable translation for “God.” But let us address the question: What if “Chi” as used in Igbo names is understood as an abbreviation for “Chineke,” “God?” There is an argument to be made there. However, that reasoning has two major flaws. The first is that when you say “Chi” instead of saying “Chineke, you will be conflating two words with varying, and possibly, opposing meanings. That can easily confuse your audience. The second is that since all references to the Christian God must be capitalized, names like Kelechi and Ọlụchi would have to be spelled funny: KeleChi; ỌlụChi.

In conclusion, let me also add that all the confusion about chi and God/god could have been avoided had Christians called their “God” by his personal name because he has one, Jehovah! Jehovah is the accepted English rendering of the biblical God. Native Igbo speakers understand that clearly. In the Igbo bible, God's name is spelled, "Jehova." Have you heard any Igbo person say, “Chi bụ eze” as a standard expression? But I am sure you hear our folks say, “Jehova bụ eze” all the time. There’s a reason for that! "Jehova" is a proper noun. "Chi" is not. Like I outlined earlier, this problem was created when European Christians used "God" as a proper noun while "god" was not. That discrepancy confused and conflated the meaning of "God/god." With a proper understanding of these terms, however, it is difficult to assert that "Kelechi" means "Thank God." And if you consider that Igbo people named "Kenechukwu" also translate that name as "Thank God" you will see how a Christian perspective rather than the true meanings of chi or chukwu interferes with the meanings we assign these names.

End notes:

Chi – Any god or supernatural entity/force (which may include the Christian God, if you like). But that would put “God” in the same category as other deities called “chi.” The Abrahamic tradition insists that their “God” is the one-and-only and very jealous of his status. He wouldn’t share a category (such as chi) or pantheon with any other deity.

Chineke – The rendering of the capitalized Christian “God” in Igbo bible.

God/god – English title/category for (any/all) divinity. “God” is not the name of Abraham’s god.

Jehova – Igbo translation for the personal name of Abraham's god originally rendered as "YHWH" ie Yahweh (Aramaic) or “JHVH” ie Jehovah (English) in Exodus 6:3; Psalms 83: 18 etc.

*The terms, Christian God and Abraham’s God/god are used interchangeably.

New Paragraph

New Paragraph

New Paragraph

New Paragraph